Game six of the World Series between the Texas Rangers and the St. Louis Cardinals was postponed because of rain. Cardinals manager Tony La Russa said he would use the night off to see “Moneyball,” the movie about data analytics in the major leagues.

Moneyball, Schmoneyball. What La Russa really needs is a primer on information theory a la Claude Shannon. Some reporters covering the series could benefit too.

During game five of the series, some costly telephonic miscommunications occurred between La Russa or pitching coach Dave Duncan (in the dugout) and bullpen coach Derek Lilliquist (in the bullpen). At various times during two phone conversations, three pitchers’ surnames were mentioned or heard or both. Those surnames are Motte, Lynn, and Rzepczynski (zep-CHIN-ski). The miscommunications yielded the farcical situation of a pitcher entering the game to issue an intentional walk to the only batter he would face. (A chronology of this comedy of errors appears at the end of this post.)

Much has already been written about these events, including commentary on La Russa’s aggressiveness in deploying relief pitchers, the quaintness of land lines that connect dugouts to bullpens in major-league ball parks, and the difficulty of hearing a phone call while 50,000 nearby fans are screaming.

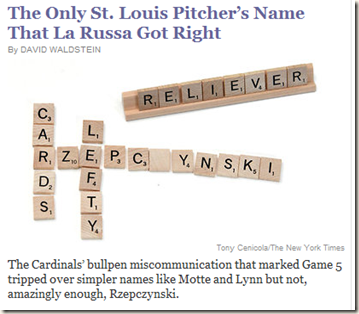

Because game six was postponed, sportswriters continue to discuss the game-five debacle. Thus we get this story in Thursday’s New York Times, accompanied by the following graphic:

The story—and the caption in the graphic above—suggest that of the three names, Rzepczynski’s is the most likely to be mis-communicated because it is hardest to say. This analysis does not comport with what we know about information theory. It is thoroughly un-amazing that Rzepczynski’s name was conveyed successfully.

Likewise, it is not terribly surprising that Motte’s name was misheard. You’re just asking for trouble if your name rhymes with “not.” Lynn’s name rhymes with “win,” “in,” and “I cannot hear your instructions over the stadium din.”

But it’s not really about rhyming; it’s about information distance. The problem with Motte’s name is that it is a short information distance to any number of other words that might reasonably uttered during a conversation about baseball: not, hot, got, dot. Lynn’s name has the same problem. Rzepczynski’s name emphatically does not.

If the bullpen coach mishears a single consonant of Motte’s name or Lynn’s name, he might reasonably believe that he heard another word; miscommunication can result. But if he mishears a consonant or other small portion of Rzepcnynski’s name, so what? He’s very likely to get the message anyway.

Case in point: Did you even notice that I mis-spelled Rzepczynski’s name at the end of the last paragraph?

Background for baseball nerds:

And now, as promised, here is the reported chronology of some events during the eighth inning of game five:

- The Rangers are batting, facing Cardinals pitcher Octavio Dotel. From the Cardinals’ dugout, La Russa or Duncan calls the bullpen and requests that two pitchers start warming up: Rzepczynski and Motte.

- In the bullpen, coach Lilliquist hears only Rzepczynski’s name. (La Russa later said that Lilliquist had hung up too early, before he said Motte’s name.)

- Rzepczynski comes in the game to face the left-handed-hitting David Murhpy, who hits an infield single.

- La Russa notices that Motte is not warming up in the bullpen, and calls again, reiterating that request.

- In the bullpen, coach Lilliquest mishears La Russa’s words as a request for Lynn to begin warming up.

- Because Motte is not ready, Rzepczynski remains in the game to face right-handed-hitting Mike Napoli, who hits a two-run double. (La Russa had wanted Motte to pitch to Napoli.) Rzepczynski then strikes out the next batter, Mitch Moreland.

- After Moreland strikes out, La Russa removes Rzepczynski from the game and requests the next relief pitcher. La Russa believes he is summoning Motte, and is surprised when Lynn walks to the pitcher’s mound from the bullpen.

- Because the rules of baseball require that any pitcher who enters the game must face at least one batter and because Lynn is supposed to be resting his arm that day, La Russa instructs Lynn to intentionally walk the next batter with four gentle, low-stress pitches.

- Motte finally enters the game, three batters later than La Russa had envisioned.

No comments:

Post a Comment